A unique training program gives the blind a new lease on life while helping shops gain skilled, conscientious employees.

AIB's production success is the result of collaborative engineering efforts from its operators and management along with dealer Adams Machinery. Front row (l to r): operators Jesse Mora, James Sarver, Clay Stillwell, and Bob Laforet. Back row (l to r): Les Anderson, AIB product and services business manager; Kris Anderson, supervisor; and Richard Short, president of Adams Machinery.

Operator Bob Laforet is legally blind, but he's fully capable of loading, unloading, and running his machine.

AIB uses special low-profile fixturing that allows for high part density. It groups left and right-hand versions of the same part on one pallet.

Scott Hornbeak, applications manager for Adams Machinery, checks the control panel of one of the Daewoo DVC 320 VMCs. He was part of the team that helped AIB integrate CNC technology into its production facility. /h4>

One safety feature that AIB thought was necessary was an auto-close palm button that requires operators to use two hands to activate a machine.

Les Anderson, product and services business development manager for AIB, holds a litter, which the company produces for the U.S. military at a rate of 850-1,000 a week.

When one walks into the machine shop of Arizona Industries for the Blind (AIB), it's hard to tell that the operators are legally blind. They're moving around the shop quickly and competently, loading and unloading a variety of parts on several advanced CNC machines. The environment isn't much different than other machine shops in the U.S. That's what Les Anderson, product and services business development manager for the Phoenix-based AIB, wants the manufacturing industry to understand.

"Shops struggling to find skilled workers shouldn't shy away from hiring the blind," asserts Anderson. "Employers may think blind workers would be a huge burden and expense on their businesses. But they're not. I would put our people up against any other operators out there. They are hard-working, conscientious employees that remain more attentive and in tune with the process than many sighted workers."

In some cases, operators already have machine shop experience. "A lot of educated, skilled individuals have lost their sight," says Anderson. "As we get older, any one of us can go blind from an eye disease, diabetes, or accidents. And there's a large population of aging machinists out there."

Anderson envisions AIB as a trade-school approach with the added ability to provide real-world experience and working conditions. "We're teaching our students to be good operators and process managers. They're learning the logistics of machining, such as how to set up their work area to be productive, how to manage their counts, and how to monitor quality levels."

The training program goes far beyond learning how to operate a machine. It also teaches the blind about getting to work on time, filling out time cards, and handling a slew of other operational details. The goal of those that run the program is to train and mentor its blind clients in all the life skills and encourage them to go forth into the world.

Paying its way

AIB's mandate is to serve as a visual rehab (VR) training program, preparing blind clients for careers in the sighted world. But the state agency is not funded by the government and must be self-sufficient to survive. " We have a dual function," comments Anderson. "We have to train, but the only way we can keep our program alive is by making a profit."

In the past, the facility did this by producing commodity items — mops, textiles, and so forth — for the U.S. government. But such career paths are limited and vulnerable to outsourcing. To overcome these obstacles, AIB shifted to modern CNC manufacturing two years ago, when Anderson joined the program.

Anderson came to AIB with a background in modern manufacturing methods. What he found at AIB was a shop using circa-1950 drill presses to produce litters/ gurneys for the Dept. of Defense (DoD). It was having problems meeting required production volumes, and internal quality costs were high. In addition, the shop had limited capabilities to competitively bid on new jobs. Therefore, it had to take a different approach to support itself.

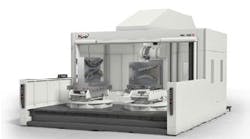

At the time, AIB was producing 720 litters every three to four weeks, but the military soon upped its order to 720 every two weeks. To meet these higher volumes, AIB needed vertical machining centers with indexing tables that let operators load and unload parts without slowing production or stopping machines. Popular in many small shops, offline load/unload negates a huge competitive disadvantage for AIB: Blind operators simply need more time to fixture parts than sighted personnel.

At the time, AIB was producing 720 litters every three to four weeks, but the military soon upped its order to 720 every two weeks. To meet these higher volumes, AIB needed vertical machining centers with indexing tables that let operators load and unload parts without slowing production or stopping machines. Popular in many small shops, offline load/unload negates a huge competitive disadvantage for AIB: Blind operators simply need more time to fixture parts than sighted personnel.

Seek out engineering expertise

"I came from a production background, and I would tell other shops to exploit the engineering experience of their suppliers," remarks Anderson. "Have them help you with fixture building, for example. Often, you're so busy running your shop that you don't get out and see the good ideas out there. That's why I think it's important to develop a good team, from the rawmaterial provider, to the machine vendor and integrator, to the fixturing and tooling companies."

Adams Machinery, Tempe, won the contract to be the lead integrator for the project. Adams collaborated closely with Anderson and Mike Hinkel, an AIB engineer who is legally blind. "He and others in the group gave us feedback on what they needed to operate a machine," says Richard Short, president of Adams.

Short and his team worked with builder Daewoo Heavy Industries, America Corp., West Caldwell, N.J., to install European-style doors, similar to those on an elevator, on four Diamond Series DVC 320 VMCs. Daewoo specially built these machines for AIB since this option isn't standard in the U.S. Adams also integrated a special auto-close palm button that requires two-handed operation and an audible system that signals when a machine cycle is over.

Safety wasn't the toughest challenge, however. Balancing workflow was.

Because AIB makes complete litters, it must carefully match quantities to avoid producing excess parts. Each litter requires two poles, four bolt blocks, and two couplers as well as four stirrups (two lefts, two rights) , four spreader bars (lefts and rights), and four saddle blocks (lefts and rights). To ensure the right numbers, AIB and Adams worked together to match and size machines and fixtures; they even balanced loads by putting lefts and rights of the same parts on a single pallet.

AIB's workholding was the result of a collaborative engineering effort. " We went to several fixture builders," recalls Short. "We had a prerequisite on the purchase order that they had to load parts with their eyes closed." Adams eventually enlisted the expertise of Bayer Systems, Phoenix, to make the fixtures.

The fixtures were designed with an eye toward the blind, but they would work well in many production facilities. The air/hydraulic fixtures are flat, with wedge-type clamping that allows chips to freely wash out. They use spring pins to snap parts in. If they don't snap, the operator knows there's either a chip in the way or he didn't push the part down far enough. And the final step was guaranteeing components load in only one direction.

"Anyone capable in the quality disciplines would tell you to foolproof operations to your best ability and not rely on chance or skills," comments Anderson. "Even sighted operators can put parts in upside down. This type of fixturing would be effective in any shop."

Successful operation

Since the installation, AIB has increased production to 850-1,000 litters/week and increased the customer base. A run of this size would have been impossible using the old equipment, according to Anderson. "We would have had to pass on the work," he says. "And when you turn down the DoD, it finds suppliers elsewhere." The AIB facility has also won a contract to produce field-surgery tables for the Army.

The group is always looking for new customers. "We're not the type of shop you would come to for a 10- piece order, where setups are intensive," says Anderson. "We hope to work with prime contractors who have a requirement to do a certain percentage of business with an organization like us. We may surprise some groups with what machining jobs we can handle."

In addition to its machining capabilities, AIB's Production Services Unit offers project management, from product design to development; process engineering services; and order management and fulfillment. Besides its machine shop, AIB has an assembly and packaging department as well as a sewing department.