Blue Chip Engineering, a Minnesota job shop, recently engineered and machined a mobile sculpture that has been presented as part of the award package for an international design/engineering competition. The Buckminster Fuller Institute named the winner of its Buckminster Fuller Challenge, an annual competition that presents a $100,000 prize “to support the development and implementation of a strategy that has significant potential to solve humanity's most pressing problems.” Along with the monetary award, the winning entry will be presented a trophy in the form of OmniOculi, a sculpture designed by artist Tom Shannon.

Rick Denny, Blue Chip founder, reported that the Buckminster Fuller Challenge award sculpture, comprised of two spheres, has been the most challenging of Shannon’s sculptures. “The upper sphere, eight inches in diameter, with a wall thickness of a quarter inch, has 1,100 holes of 16 different sizes, and it is designed to rotate or spin on a shaft attached through roller bearings to the supporting lower, four-inch diameter sphere.”

Tom Shannon intended for the sculpture to reflect several relationships to Fuller’s architectural concepts — physically and optically — two of these concepts being geodesic geometry and harmony with the environment.

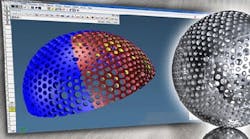

Also, to perform as “an interactive optical instrument,” Shannon called for the internal and external surfaces to be mirrors that would reflect the environment within and without. To create the relationship to geodesic polyhedrons, Shannon called on scientific designer and geodesics expert Joe Clinton, who used CAD programming to develop a hole pattern that achieves the intended effect.

Clinton supplied the design and “seed pattern” for the holes to Blue Chip Engineering in a Cadkey file. Then, Denny transferred the CAD program into SolidWorks to create a solid model, duplicate the hole pattern across the spherical surface, use mass properties to physically balance components, and supply machinable models for programming a 5-axis machine tool with GibbsCAM.

GibbsCAM programs support 2- through 5-axis milling, turning, mill/turning, multi-task simultaneous machining and wire-EDM. The software also has fully integrated manufacturing modeling capabilities that include 2D, 2.5D, 3D wireframe, surface, and solid modeling.

The upper sphere of the sculpture had to be machined as two hemispheres. The two pieces could not be brazed or epoxied together because access to the interior surface would be required for dusting or re-polishing. This created the most difficult part of the project, which was matching the two halves while maintaining continuity of the hole patterns. Once resolved, machining could begin.

As with all Shannon sculptures, the visible, and reflective, components begin as solid 2024 aluminum billet. Denny said general machine programming for the job was fairly simple, but programming the holes “would have been a nightmare, had it not been for the combination of SolidWorks and GibbsCAM, which give us a lot of power.”

GibbsCAM’s Hole Manager utility simplifies and automates holemaking operations, condensing the task just three mouse-clicks, according to the CAM developer. Hole Manager automatically recognizes holes by characteristics assigned within SolidWorks, puts a point at the center of each hole, and provides a normal vector to the hole.

The points and normal vectors are used by GibbsCAM to program the proper tool rotation to perform the specified hole operations – boring, drilling, tapping and countersinking. It is especially useful when holes to be made are on multiple planes, such as the infinite number of possibilities presented by spheres. “Programming 1,100 holes for 5-axis machining was still difficult, and I spent a lot of time doing it,” Denny recalled, “but it wasn’t the nightmare it would have been without SolidWorks and GibbsCAM.”

After machining, polishing each hemisphere was quite time-consuming, requiring several steps with progressively finer grit, to leave perfectly spherical reflective surfaces. As with procedures using SolidWorks and GibbsCAM, Blue Chip has developed processes for polishing to pass Tom Shannon’s scrutinizing eye. Even so, after polishing each hemisphere the shop spends five hours cleaning to remove polishing compound from all of the holes. “You just sit down with an electric drill and a million Q-tips, and get it done,” Denny said.

The patience and attention to detail pay off because Denny appreciates the engineering, programming, and machining challenges that emerge from working with Tom Shannon, and the association of his work with worthwhile causes.