With so much focus on worries about American products being uncompetitive with those produced elsewhere in the world and the associated impact on jobs and domestic economic activity, it is easy to forget that there are a number of manufacturing sectors for which American dominance has persisted for decades and shows very few signs of ebbing.

Perhaps the best example is the aerospace sector.

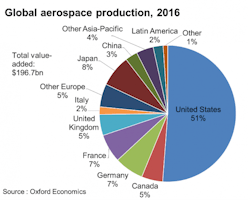

The United States currently accounts for half of global production (with Canada adding another 5%). While this share has declined substantially from close to 70% in the 1980s and 1990s, the reasons for the decline are mainly due to the expansion of Airbus (particularly since the introduction of the A320 in 1987) and consolidation in the U.S. when McDonnell Douglas merged with Boeing in 1997. The Boeing-Airbus duopoly has meant that North America and Europe accounted for nearly 90% of global production through to the financial crisis, although that has fallen to 82% today.

The aerospace industry is a good business in which to be competitive, because the underlying drivers of demand are very strong. Since the end of the Great Recession, new commercial aircraft orders have typically been double, and in some years triple the number of annual deliveries. This reflects explosive growth of air traffic in the emerging world as rising incomes and declines in ticket fares make air travel affordable for increasing numbers of households.

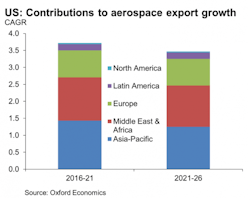

Global air travel has increased by 6.5% per annum since the end of the financial crisis, and this growth in Asian passenger traffic in particular has accelerated in the past two years. The drop in crude-oil prices has driven global airline profits to historic highs as operating costs pressures ease and increase scope for further investment in fleet modernization. Continuation of these trends means that global aerospace production is expected to grow by 3.5% per annum for the next ten years, almost a percentage point faster than global GDP.

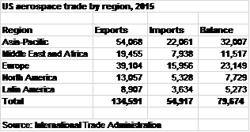

These geographic patterns of production and demand are mirrored in U.S. aerospace trade performance (which includes not only finished aircraft, but also parts and components that feed into supply chains of aircraft manufacturers). The trade surplus in aerospace products reached $80 billion in 2015 on exports of $140 billion, both record highs. This surplus, which has widened in the past 15 years both in absolute terms and as a percentage of aerospace exports, keeps the total U.S. trade deficit 10% smaller than it otherwise would be. China became the most important single destination in 2013 (passing Japan and the large European economies), but still only accounts for 10% of the total. But on a regional basis, the Asia-Pacific region accounts for 40%, with Japan, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan being other important destinations. This is a function of both stronger short-haul travel within Asia and expansion of longer-haul routes to Europe and North America.

A key question, of course, is the degree to which the competitive dominance of the U.S. aerospace industry will persist. There are many reasons to be optimistic, the first and foremost of which is a well-earned reputation for reliability and safety. This is a big part of the reason that, despite concerted efforts by China to develop a commercial airliner to compete with Boeing and Airbus, its share of global output is only 3%. Furthermore, test flights of the Comac C919—a short-haul commercial airliner manufactured by the Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China—have been delayed, and most observers agree that its cost-efficiency, comfort, and safety will be insufficient for it to challenge the Airbus-Boeing duopoly. We do not expect China’s share of global aerospace production to exceed 5% for the next 15 years.

A second factor is history. The U.S. was the birthplace of aviation, and geography has always favored the sector’s development thanks to a relatively large landmass with a widely dispersed population that is conducive to air travel. Geopolitical history has only reinforced that advantage, as that has encouraged heavy investment in the R&D, engineering and production infrastructure to create industrial clusters in Seattle, southern California, Kansas and elsewhere. This is one of the key reasons why U.S. aerospace manufacturing remained so dominant against European manufacturers such as de Havilland/Hawker, Fokker, Aérospatiale and the other predecessors of Airbus.

For all of these reasons, the already-soaring U.S. aerospace industry is set to fly higher, with export growth expected to average a bit more than 3.5 % over the next decade. This demand, along with a relatively robust outlook for air travel in the domestic market looking ahead, means that U.S. aerospace will maintain, if not slightly increase, its dominant share of global production.

Jeremy Leonard is Director of Industry Services at Oxford Economics, an independent global advisory firm providing reports, forecasts and analytical tools on 200 countries, 100 industrial sectors and over 3,000 cities.

This article was originally published on IndustryWeek a companion site of American Machinist and part of the Penton Manufacturing & Supply Chain group.