Heavy turning of "gummy" metals usually forces machine shops into a triage dilemma: they have to choose to emphasize cycle time performance, or chip control, or tool life, but they will not get all three of these goals at once, or even two of the three. Cutting deeper improves chip control and speeds up the operation but raises the risk of rupturing the tool at any moment. Cutting shallower may prevent tool rupture, but it slows down the operation, requires more passes and can create long, stringy chips -- with all the associated baggage.

There is no triage needed at AWC Frac Valve in Conroe, Tex., which manufactures very large valves for the oil-and-gas industry -- and generates chips the size of cornflakes in the process. With a 35-man shop running 24/5, the company is a division of Archer Well.

By retooling a heavy-duty OD turning and facing job in 4130 steel (a material described memorably as "gummy"), the shop tripled the material removal rate and more than doubled tool life. Moreover, it completely eliminated the sudden edge failures that had interrupted production before and forced a lot of re-working.

“Previously we had to keep two back-up tools in the turret just to keep things going when one tool popped,” recalled Jim Beaver, assistant production manager. “Often the tool would rupture midway through the first piece.”

The new tool is an advanced, indexable coated-carbide insert developed by Ingersoll Cutting Tools, the CNMX Gold Duty. With a radically aggressive top face geometry, in an advanced seat pocket scheme, it is a generation ahead of the field in large-scale turning, according to Ed Woksa, Ingersoll national turning product manager. AWS is one of the first users of the new insert, he added.

Now the big chips peel off in easily controlled “sixes and nines,” reducing a 480-lb. billet of 4130 steel to a 250-lb. valve bonnet in about 45 minutes on a Doosan 400LM turning center. The job used to take up to two hours to complete – and usually shattered one tool per part.

The retooling began when Jim Beaver set a new tool-life requirement for the operation: two pieces per edge, minimum. The standard insert at the time, an older conventional CNMG negative-rake tool, rarely lasted through one part.

The new requirement was part of a plant-wide “Continuous Improvement” initiative that Beaver was charged to implement.

He pointed out the challenge to Ingersoll’s Mike Salewsky during their regular weekly plant walk-through. Because of the scale of the operation and the cutting forces involved, Salewsky brought in Ingersoll field turning product manager Eric Strieby. The new- generation CNMX tool he recommended was just being commercialized at that time, so Streiby offered a free, no-risk on-site test.

“It was like a beta test, but on a commercialized tool,” said production manager Kirk Cudd. “Should the tool break during the test, we wouldn’t have to pick up the tab.” By contrast, many tool providers offer on-site testing and reduction to practice, but only after the customer purchases the tool and pays for any replacements.

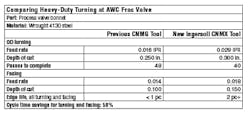

CNC lead man Ben Molinar ran the test on live parts, on site, with Ingersoll guidance: heavy OD roughing, OD finishing, and facing on 4130. (A comparison of the results appears in Figure 1.)Once the tool proved out operationally at the parameters established in the test, Beaver did some fine-tuning. He eliminated the two back-up tools from the turret and ramped up the depth of cut to 0.325 in. for turning and 0.225 in. for facing. Still, the inserts lasted through at least two parts with absolutely no ruptures. “Now the failure mechanism is gradual wear, not fracture, and the indicator for edge change is simply loss of finish,” said Jim Beaver.

Not surprisingly, tool-related production stoppages disappeared altogether and tool servicing labor costs dropped significantly. He puts the annual all-in saving associated with the retooling at $75,000 for this job alone.

The Ingersoll CNMX tool succeeded by combining improved top face geometry, versus conventional CNMMs and CNMGs, with an advanced seating system that makes the new geometry possible. “You can see the big wide front edge that really breaks up the chips on a pretty gummy metal,” said Jim Beaver.

Here’s a closer look: CNMMs are neutral-rake with a negative land at the cutting edge for added strength, better chip breaking and improved chip flow. This allows higher feed rates to be applied. But, they must be single-sided because you can’t flip a positive-rake tool without damaging the cutting edges with the clamping forces.

By contrast, CNMGs that are designed for heavier cuts are two-sided but normally have neutral or slightly positive rakes (0 to 6 degrees), which raise cutting forces. “The new seating arrangement in the CMMX makes it possible to get two sides plus aggressive, positive geometry in the same insert – something never available before,” said Ingersoll’s Ed Woksa. “Thus, you can cut deeper without overloading the insert, and still get the second side.”

Unlike flat insert seats found with conventional toolholders, the Ingersoll CNMX seating scheme is based on four “rest pads” on the insert that mate with dimples in the seat. So it’s the rest pads and not the cutting edges that bear the clamping forces. As a result, the cutting edge can be 5 degrees positive, for freer cutting, without risk of clamping damage.

“Tooling performance aside, Ingersoll was easier to work with on a very risky operation,” Beaver said. “Besides, we were looking for a tool-life improvement only and wound up with a cycle-time saving as well.” Looking ahead, he sees at least ten other heavy turning jobs where the new Ingersoll CNMX would likely bring about the same improvements.