For longer than most of us remember, long-reach machining has brought headaches to manufacturers. That’s the bad news.

The good news is that recent tooling innovations ease the pain over a wide range of applications. Today you can have a stable contour milling operation 22 inches deep inside a hardened steel mold cavity or stainless steel turbine bucket. Today you can open large holes deep down between the webs in steel castings, and face-mill deeply recessed flats in iron castings – 3 to 5 times faster than before, with none of the usual chatter, much less risk of sudden tool rupture.

There’s more. Today, medical device manufacturers have a stable process for boring 4:1 aspect holes in thin-walled titanium — an application that has stymied conventional boring tools for more than a decade.

And today, alert plastics fabricators are routing out deep recesses in their moldings twice as fast.

“No single tool meets all such diverse long-reach challenges, but those that do usually share two common features: high-feed insert geometries and extra-rigid shanks and extensions,” said Konrad Forman, North American milling product manager for Ingersoll Cutting Tools. “That said, the right choice for a particular long-reach application would hinge mainly on the geometry of the cut to be made.”

By and large, high-feed insert geometries cut faster while reducing lateral cutting forces that can trigger chatter leading to sudden tool failure. More rigid shanks reduce both chatter and runout all the way to the bottom of the cut.

Improved Mold-Cavity Hogging

Some of the greatest successes come from die and mold manufacturing, with its familiar diet of contour milling deep in the cavities within hardened steel mold blocks. Recent market trends driving demand for larger, deeper molds simply intensify the problem. “Mold cavities typically are 5-8 inches deeper than just five years ago,” explained Jay Noble, lead machinist at Redoe Mold Ltd., Windsor, Ont.

These days, Redoe finish-mills 15- to 22-inch-deep pockets in half the time as before, with no sudden edge breakdown. The new tooling package is an Ingersoll Form MasterV high-feed cutter mounted on an advanced Ingersoll Inno-Fit shank extension.

In high-feed milling, the tool feeds faster while taking lighter cuts. The metal comes off faster, but at lower cutting forces, especially the lateral forces that complicate long-reach work. High-feed inserts are typically triangular, with low lead angles (10-20 degrees) relative to conventional inserts.

A critical aspect of the Inno-Fit shank’s extra rigidity is a self-centering, three-point coupling design, enlarged contact area between the mating surfaces and an extremely wear-resistant material of construction. By contrast, most conventional shank extensions use a slide coupling system.

Chicago Mold Engineering takes a different approach to small deep cavities. It uses an Ingersoll Hi Feed Mini Cutter, one of the smallest milling tools available with the high-feed geometry. As a result, the St. Charles, Ill., moldmaker is able to complete a semi-roughing operation more than twice as fast as before. The new tool has more flutes than the previous one, reducing the cutting force per flute without slowing down the operation. With the lower lateral cutting forces, the shop is getting good results with a less expensive standard extension.

Machining the buckets in big hydropower turbines is an almost 100% long-reach effort, always posing the risk of chatter that the specs would not allow. Accordingly, Canyon Hydro in Sumas, Wash., did everything possible to eliminate “chatter triggers” from the start in its new, lights-out, six-axis machining facility.

Termed “runners” in the powergen industry, these turbines may measure up to 11 feet long and lose a ton and a half of metal in a three-month 24/7 long-reach milling process. Almost all machining is done with 19-inch extensions, yet all as-machined surfaces must be smoother than 32µ and geometrically correct within 0.010 inches.

Canyon and Ingersoll worked together on the total tooling package, emphasizing accuracy and finish above throughput. For smaller turbines, the tool of choice is an Ingersoll FormMaster Pro, specially designed for stable long-reach roughing and finishing. Besides using a free-cutting, high-feedgeometry, the three-flute tool features serrated inserts in a timed array that ‘nibbles’ away the metal, progressively. Each insert is located “five minutes” behind the other in the pitch circle, so each edge engages a different part of the toolpath. The operation runs twice as fast as before, holding all tolerances -- lights out.

Larger runners involve some undercuts along with 20.5-inch extensions. Accordingly, the undercuts are done with a modified standard FormMaster Pro button cutter with additional cutting surfaces on the top. It works like a high-feedbutton cutter for most of the cut, then as a T-slotter to complete the undercuts as it is withdrawn. The improvement on the big runners is about the same as with the smaller ones, again holding all specs.

Big Holes, Deep Down

Large, long-reach holemaking has been improved with high-feed tooling, too. Recently, Baldor Electric Co. used it so successfully that it has since applied it to 10 different jobs, and is considering applications at several other plants.

The first application involved large, cast steel housings with holes to be opened more than 10 inches down between the webs. Previously, Baldor accomplished this with a solid-carbide endmill in an orbital toolpath. Now, it’s done with a high-feed Ingersoll Deka mill in a corkscrew orbit. The process and tooling switch tripled the material removal rate and improved tool life by 20 to 1.

The gain stems from the Deka’s high-feed geometry plus the orbital toolpath, which advances through the work -- from the solid (no pilot holes needed) -- without the stop-and-plunge delays inherent in orbital milling. Moreover, the indexable tool reduces the engagement area with the work, and the resultant lateral forces.

If the experience at Medfab Manufacturing is any indicator, long-reach boring in tiny parts needn’t be the problem it once was. That Lakeville, Minn., shop described its challenge as a machining “perfect storm”: ID machining, thin walls in titanium, 4:1 aspect ratios and a 16µ surface finish spec. The workpiece is a 1-inch long x 0.25-inch diameter piece of titanium tubing, with walls thinner than your fingernail.

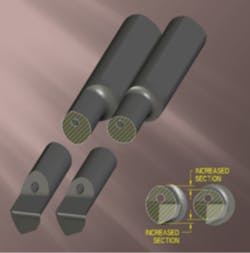

The remedy is a very advanced boring bar with a novel elliptical cross section, through-the-insert coolant delivery and high-feedtip geometry. It is called the Ingersoll T-Micro boring bar. The long axis, aligned with the cutting tip, provides additional rigidity and vibration control. The short axis expands the channels for chip disposal.

Cycle time with all previous boring bars was 3.5 minutes – followed by 15 minutes of hand polishing on every single piece to reach the 20µ ID finish spec. With the T-Micro boring bar, cycle time was reduced to 3 minutes, as-machined surface came in at 8-10µ (even on the 250th piece), and all hand finishing was eliminated.

Based on that success, Medfab now uses the T-Micro cutter on tantalum, MM35P (machinability like Waspalloy), and other high-nickel alloys.

Deep Between the Webs

Long-reach work on flats benefits from the same high-feed, free-cutting insert, but in a different presentation, according to Forman. The proof of this the skinning and plunge-milling of the bosses 15 inches down between the webs on big iron castings at Hol-Mac Inc., Bay Spring, Miss.

During such an operation a few years ago, an insert ruptured, triggering a tool wreck that blew out the spindle before the operator had a chance to shut down. Manufacturing engineer John Scarborough looked for alternatives and settled on a facemill that orients the inserts tangentially — an Ingersoll S-Max. The switch not only wiped out all catastrophic tool failures, but it also doubled throughput on more than 20 different long-reach jobs.

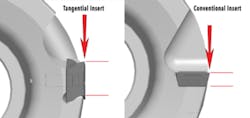

In tangential milling (TM), the inserts lie flat in the pitch circle, not upright (see diagram). This presents the insert’s strongest cross-section to the main cutting force vector, leading to a more durable cutting system even in long-reach conditions.

Today’s TM mills can handle limited ramping as well as flat work, Forman said.

Though cutting forces in plastics machining are obviously much lower than in metal, high-feed tooling is making a difference in long-reach applications there, too. One Illinois plastics fabricator reported a 30% improvement in enterprise-wide machining throughput following the switch from solid high-speed steel (HSS) tooling to indexable tooling. Ingersoll high-feed indexable routers are completing long-reach operations in half the time as HSS cutters, and outlasting them more than 20 to 1. Some carbide tools look as good as new after more than a year in daily service.

“This success could be a wake-up call for plastics fabricators still married to high speed steel tooling,” Forman said. “Carbide tooling does involve an up-front expense for the cutter bodies, but it delivers a quick payback in higher throughput and much longer tool life.”

According to Forman, the gain in efficiency stems from a combination of factors: carbide’s far superior strength and wear resistance over HSS, the high-feed geometries possible in pressed carbide inserts that cannot be cut into solid carbide endmills, and the larger cutter diameters possible with indexable inserts in steel cutter bodies. The larger pitch circles take advantage of chip thinning to enable faster feeds and to create a gentler entry angle into the cut, he explained.

“Requirements for long-reach machining will never go away, but with updated tooling solutions and practices, the headaches can,” Forman concluded, “and help is available for the asking.”