Race teams that compete in the National Association of Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR) Cup Series put demands on their machine shops that most machinists would consider impossible or, at least, unreasonable.

To be among the best in your profession, you need to identify those who are considered the best, then figure out what they did to get there.

In machining, shops that are able to deliver quality products on time are considered to be among the best, and when it comes to delivering zero-defect parts with lead times that most shops consider impossible, nobody does it better than the machinists who work for NASCAR.

Because the failure of any one of the hundreds of machined parts that go into making a NASCAR Cup car could cost the team millions of dollars in lost revenues and diminished sponsorship, every part must be made perfect.

Race teams constantly redesign and fine tune their cars to make them more competitive. Parts for those cars and, therefore, the CNC software programs used to machine those parts, are constantly altered. And, because engineering changes are driven by race track performance every weekend, the lead time for producing redesigned parts is reduced to days and sometimes to hours during the race season.

While many shops have difficulty keeping up with part delivery when lead times are measured in weeks or months, NASCAR machinists find ways to be productive so that they deliver their products to support the success of their teams.

Nearly every team that competes in the NASCAR Cup Series is based within 90 miles of Charlotte, N.C., and several racing teams opened their doors to provide an extensive behind-the-scenes look at their shop operations.

Haas CNC Racing (www.haascncracing.com), Hendrick Motorsports (www.hendrickmotorsports.com), Joe Gibbs Racing (www.joegibbsracing.com), Richard Childress Racing (www.rcrracing.com) and Roush Yates Engines (www.roushyates.com) all contributed to this article.

When you walk into the assembly area at Joe Gibbs Racing, you are nearly blinded by the spotless bright white floor. Like every facet of their operation, the floor color was chosen because it offers a competitive advantage over using other colors. The floor is white because it provides more light to the mechanics who work on the cars and makes their jobs easier and makes them more efficient. All of the shops visited had white or light gray floors for the same reason.

“We operate as a captive machine shop for a mediumsized manufacturer,” Kelly Collins, director of manufacturing at Joe Gibbs Racing said.

“The company has 450 employees including 18 machinists who work a shift-and-a-half. Typical part runs are 2 to 20 pieces with some longer runs for parts that are common to all the cars and don’t change much.

“Our lead times on new parts are measured in days, sometimes in hours. We came out of the race in Charlotte last weekend with a bracket on the car that was causing a problem. We had to completely redesign and manufacture a new bracket in two days to have the car ready for the race next weekend.

“That’s typical on part failures, which don’t happen that often. Our engineering people do a lot of Finite Element Analysis on all our parts to make sure the parts can meet the demands of racing,” Collins said.

“We evolved from the ability to make a few parts here and there and purchasing the rest to manufacturing most of the parts and having an engineering staff that designs parts all day long while we program new parts all day long and manufacture those parts,” Collins said.

“We have become a traditional manufacturer with an engineering group, programming group, materials management group and use the whole Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) process with order entry, material planning, etc. We now have a Mitsubishi laser and waterjet, two wire EDMs and a sinker EDM all from Mitsubishi along with 14 Doosan mills and four Doosan lathes. Two of the Doosan lathes have live tooling, and one lathe is a dual spindle. We use Siemens NX software throughout the company.”

Collins said that the process for acquiring new machines starts with identifying a need for the machine, then looking at the market to identify the machine tool that will fulfill that need. Then, the race team approaches machine tool manufacturers for sponsorship.

In the case of machine tool companies, sponsorship usually involves providing the racing team with equipment in exchange for advertising benefits and the opportunity for the manufacturers to bring prospective clients into the racing facility to see the machines in action.

Collins said that if they cannot get a machine tool through sponsorship they will do whatever it takes to get the machine to give their race team the competitive advantage.

The Joe Gibbs shop used to have work cells that included mills and lathes, but it has evolved to workcells organized by machine type.

“We did a workflow analysis to see how we could improve our workflow,” Collins said.

“We found that having a lathe and mill cell was less efficient than grouping like machines together because we could store tools and fixtures in one central location to prevent the tools from being spread all over the floor and wasting operators’ time trying to find them. Now we have all our mill tools and fixtures with the mill cell and all the lathe tools and fixtures with the lathe cell,” he said.

Joe Gibbs Racing also implemented Exact Software’s (www.exactamerica.com) JobBoss shop floor control software.

“The software keeps the schedule in front of you, helps to coordinate departments, and we don’t drop as many balls,” Collins said, adding that the shop uses the JobBoss program for a variety of functions.

“We actually schedule CNC programming, coordinate and schedule incoming material, gauge capacity problems by work center to see where we are over or underloaded, and we are are able to move people from mills to lathes or back again to balance our workflow. I can see, in priority order, what needs to run across my equipment by date and work center,” Collins said, adding that the shop uses barcodes to track labor.

“I can look at my reports and know they are in real time and accurate. That helps me keep our customer departments updated with the status of their jobs.”

Joe Gibbs Racing puts Toyotas on the track. The race team develops its engines with Toyota support and works to continually improve performance based on analysis and test results.

As with other NASCAR teams, the Joe Gibbs team strives to make its cars go better, and when the difference between first and last place can be as little as three tenths of a second, every little bit helps.

Winter is the busiest time for NASCAR machine shops. It’s the off-season for racing, and the teams develop and redesign many parts for their cars to ready them for the Daytona 500, the race that launches each new season.

The machine shop at Richard Childress Racing serves the needs of five racing teams. It runs one shift, 7a.m. to 4 p.m., 5 days a week, and has 8 machinists.

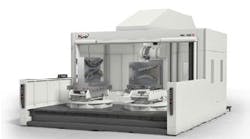

The Richard Childress Racing shop is the host for an Okuma Technology Center, and has four vertical machining centers, three turning centers, three 5-axis machining centers and two 500-mm horizontal machining centers all from Okuma. The shop also runs a Sodick EDM and a waterjet from Omax. Okuma uses the facility to show prospective customers the Okuma machines in a production environment, and it helps when that production environment is an exciting NASCAR racing team facility.

The shop runs Pro/Engineer software from Parametric Technology Corp. (www.ptc.com).

“We are a short run job shop,” Rick Grimes, manufacturing manager for Richard Childress Racing, said.

“For most parts, we have orders for two to three weeks out. When a team needs a part for next weekend, we stop what we’re doing to make that part. It can be frustrating from a production point of view, but that is the game we are in. Our average lot size is 30 to 35 pieces, and we use Exact’s JobBoss software to see the full impact of juggling or changing schedules to take care of emergency production,” Grimes said.

All of the NASCAR shops visited put their machines into groups – mills with mills and turning machines with turning machines– so that they can machine part families with better efficiency. And, all of the shops use manual machines for one-off and prototype machining.

The Richard Childress Racing shop recently moved to a 17,000-sq.-ft. facility — more than doubling its size from its previous 8,000-sq.-ft. facility. The added space gives the shop a wide aisle down its middle so that it can move machines in and out as Okuma updates its equipment. The wide aisle also makes it easier to bring large groups of people through the facility without interrupting the work flow.

The engines used by Richard Childress Racing are made by a joint venture between Richard Childress Racing and Dale Earnhardt Inc., and the Richard Childress Racing machine shop serves as a vendor to the engine building operation. The shop supplies machining as it is needed in addition to doing the other machining needed by the teams that race for Richard Childress Racing.

Grimes said the Okuma machines provide high productivity and reliable operation.

The race teams find many different ways to solve the puzzle of squeezing out greater horsepower from an engine and higher speeds from a car based on the technical requirements for each race dictated by NASCAR. The NASCAR rules closely define car parameters, and race teams work to find an edge amid the requirements.

The machine tools that each machine shop uses become part of each team’s competitive edge. The Richard Childress Racing shop uses machines from Okuma America Corp. (www.okuma.com). Joe Gibbs Racing uses machines from Doosan Infracore (http://usa.doosaninfracore.co.kr). Hendrik Motorsports fills its shop with machines from Haas Automation Inc. (www.haascnc.com). And, Penske Racing uses machine tools from Mazak Corp. (www.mazakusa.com).

Larry Zentmeyer, production manager for Hendrik Motorsports said his shop maintains a strong working relationship with Haas. His shop includes a Haas laser cutting machine that the shop uses to cut flat stock.

Hendrik is a medium-sized manufacturer that has more than 500 employees. It has more than 100 employees in its engine shop, and makes Chevrolet engines for its four teams that include two Haas CNC Racing teams.

Haas Automation designed a special machine for Hendrik Motorsports for milling engine heads. Haas Automation made two of those machines, and both are at the Hendrik facility.

Hendrik Motorsports uses Siemens NX suite of software. Zentmeyer said his shop’s complex design and manufacturing operations require consistent communication from design and analysis to manufacturing and data management, and the Siemens software fulfills its needs.

Zentmeyer said his machinists are highly skilled.

“Every machinist has been here for at least 7 years, and they all had machining experience before coming here. We have very low turnover in the shop.

“Our salaries are competitive, and we also provide intangibles such as always having the tools they need and a clean, safe working environment. We group our mills together and our lathes together so that a machinist can usually operate two or three machines at the same time. We have a couple of machines with pallet changers for ease of operation, but our production runs are small –100 pieces to 150 pieces or less — but typically around 20 to 50-piece runs,” he said.

As other shops do, Hendrik Motorsports uses an Omax waterjet to make templates, brackets, rocker stands, trim billets and cut steel, aluminum, plastics and rubber. The shop also makes carbon fiber seats and uses the waterjet to cut parts for them.

While it still uses its Haas laser cutting machine to cut thin parts, it is moving that work to its waterjet machine as well.

“We can import from a DXF file and within a minute or two we are ready to cut on the waterjet,” the waterjet operator said.

“Simple parts we can just enter on the machine control. We have to cut this 8-in. ring out of 1-in. steel. We used to drill a hole, put a band saw blade through the hole and weld the band saw blade back together before we could cut the inner diameter. Now we can cut the entire ring out of flat stock much faster.”

Hendrik builds approximately 100 new engines each year at a cost of between $50,000 and $60,000 each. Every engine gets completely torn down and rebuilt after each race. Some of the parts are discarded and replaced, while other parts are refurbished.

Cylinder blocks for the engines are cast iron, while cylinder heads are made from a variety of aluminum alloys, steel or more exotic alloys.

Cylinder head porting, the modification of intake and exhaust ports on the engines to improve the quantity and quality of gas flow, is the most sophisticated machining process that NASCAR shops face. They typically use 5-axis, simultaneous machining, and the operation often is more art than science.

In the porting process you have to be able to adapt to change and adapt quickly, Zentmeyer said.

“If the engineers find something in a port that improves performance, then we have to duplicate that on the machine shop side. We are always doing R&D to improve our engines,” he said.

“We’ve got guys dedicated to R&D, and that is all that they do. They often manually port an engine and then we scan and reverse engineer it to create toolpaths for machining. We can also start from scratch and quite often do that,” he added.

All of the Ford engines used in NASCAR racing are made by Roush Yates Engines, a machine shop that provides normal production operations in addition to its work for NASCAR. The Roush Yates Engine shop is completing the design of a new engine for the 2009 racing season. It uses Mastercam software programs for its CNC work.

Haas CNC Racing is housed in a small, two-year-old building, and it runs 12 Haas machines. The Haas CNC Racing shop was launched six years ago, but was relocated to meet the needs of the Haas race team.

Haas CNC Racing also uses Mastercam software for its CNC work.

“We’re a small shop. There are only three people in my shop, and I do most of the CNC programming,” Brad Harris, machine shop manager at Haas CNC Racing, said.

Haas CNC Racing gets its engines, engineering support, and other parts, such as a roll cage from Hendrik Motorsport.

In an industry where millions of dollars can be lost by a single part failure, these shops deliver perfect parts, often in impossibly short order-to-deliver times.

Whether it is something as simple as painting the floor white to better reflect available light or working with a machine tool manufacturer to develop a machine that will do a particular job better than anything else on the market, the machinists of NASCAR do it.

They are, as they say, “in it to win it” and anything that gives them a competitive edge gets incorporated into the way they work.